The Facts on Fats and Your Heart

Updated from original post published February 11, 2015

February is Heart Month, and while there are many dietary factors that can influence heart health, the conversation often turns to fat. For instance, Las Vegas’s Heart Attack Grill prides itself on milkshakes with “the highest butterfat content” and fries and onion rings cooked in pure lard! I’m sure many of us have heard (or even said) at least once that high fat or deep-fried foods “clog our arteries” or raise our cholesterol.

However, the tide seems to be shifting a bit when it comes to fat and heart health. The most recent USDA Dietary Guidelines no longer set a limit on the amount of cholesterol we should eat in a day. A few years ago, a systematic review that concluded that saturated fats have a neutral effect on heart disease risk sparked news headlines proclaiming that butter and bacon were a-OK. Books like journalist Nina Teicholz’s The Big Fat Surprise recommend increasing our fat intake for better health.

So is fat good or bad? Let’s take a peek at some of the evidence.

A Short Chemistry Lesson

You’ve probably heard the terms saturated, unsaturated and trans fats (or at least seen them on a nutrition label), but what exactly does it all mean? Here’s the quick and dirty:

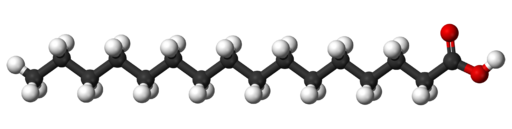

All the different fats in our diet are made up of fatty acids, which are molecules with a carboxyl group (C(O)OH) as a “head” and a carbon-hydrogen “tail”. The general groupings of fats that we know are distinguished by what the tail looks like.

Saturated Fat

Saturated fats are usually solid at room temperature (i.e. butter, lard, palm oil, coconut oil) and are so named because the carbon molecules in the chain (black balls) have all of their available chemical bonds taken up (i.e. saturated) by hydrogen molecules (white balls).

Unsaturated Fat

Unsaturated fats are usually liquid at room temperature (i.e. vegetable oils) and are so named because some of the carbon molecules don’t have all of their bonds filled with hydrogen molecules. Instead, the carbon molecules will form a second bond with each other, which causes the molecule to have a curved shape. Because the curved shape makes it difficult for the fatty acids to be tightly packed (compared to the straight, saturated fatty acids), this often means they have a lower melting point, which is why most of them are liquid at room temperature.

A monounsaturated fat means that there is only one double-bond in the molecule, whereas a polyunsaturated fat means that there is more than one.

Trans Fat

The carbons in our fatty acid chains all have four bonding points – two of them are bonding to the carbons beside them in the chain, while the other two are free to bond with hydrogens. In most fatty acids, the two hydrogens stick out on the same side of the chain. This is called a “cis” configuration. A “trans” configuration is when the two hydrogens stick out on opposite sides of the chain. Trans fatty acids are usually formed artificially through hydrogenation (more on that later) but can also occur naturally in the fat and milk of ruminants (cows and sheep).

What We Know for Sure About Fats and Your Heart

OK, now that we’ve got some chemistry out of the way, let’s talk about what happens when we eat some of these different fatty acids. Based on the current evidence, here are some of things that most health professionals and researchers can agree on:

The Low-Fat Craze is *So* 80’s

I’m sure many of my fellow dietitians would agree that it feels like nails on a chalkboard when an article or blog post claims, “Dietitians are so out of date because they still promote low-fat diets.” Dietitians are constantly updating their practice based on the latest evidence, and I think most (if not all) of my colleagues would agree that blanket statements telling people to reduce all fats are completely out of date.

The 2004 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) – Nutrition found that compared to a similar survey done in 1970-1972, calorie intake remained the same, but the proportion of the calories coming from fat decreased. In other words, after reducing the amount of fats in the diet, people didn’t just eat nothing, they replaced those calories with something else. And that something else was often refined carbohydrates (think: Snackwells, rice cakes, 100-calorie Snack Packs). Research now shows when fats, particularly saturated fat, is replaced with carbohydrates, it is associated with an increased risk of heart disease, partly because it can increase your triglycerides and LDL (bad) cholesterol, while decreasing your HDL (good) cholesterol.

However, studies show that replacing saturated fats with polyunsaturated fats (i.e. most vegetable oils) are beneficial for heart health, which is why dietary advice now promotes increasing intake of “healthy fats” while decreasing intake of “unhealthy fats”, as opposed to decreasing all fats.

Artificial Trans Fats are Bad for Your Heart.

Artificial trans fats are formed when food manufacturers take unsaturated fat and add hydrogen molecules to it (“hydrogenation”) so that they take on the properties of a more saturated fat. Food manufacturers like this because it makes the fat more shelf-stable. This is how shortening and hard (“stick”) margarines are still made. Trans fats have a negative impact on our heart health, partly because they are associated with increased LDL (bad) cholesterol and either no change or decreased HDL (good) cholesterol.

While consumer pressure has changed the manufacturing of soft (“tub”) margarines so that virtually all of them no longer contain trans fats (they are now made by mixing different proportions of saturated and unsaturated fats, and sometimes water, to create a spreadable texture), artificial trans fats can still exist in commercial baked goods and fast food. If you’re unsure, read the ingredient list and watch for “hydrogenated” or “partially hydrogenated” oils, or shortening.

The distinction between artificial trans fats and naturally-occurring ones are now being made, because there is data that shows that conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a trans fat naturally found in beef and dairy, may have positive health benefits.

Where There is Controversy

Saturated Fats and Your Heart

Recently I attended a talk by Dr. Andrew Samis of Queen’s University, where he reviewed the history of how the low-fat recommendations came to be, and the current research on fats and the heart. Everyone in the room was shocked to learn that when Americans were told to reduce their fat intake for the first time in the McGovern Report published in the 70’s, it was met with resistance from scientists at the time.

As years have passed, the dietary guidelines continue to recommend a lower fat diet despite continued lack of evidence supporting this claim.

As I mentioned earlier in this post, there was a lot of buzz surrounding a systematic review of studies published a few years ago by Chowdhury and others. It found that saturated fat intake was not associated with a higher disease risk, and concluded that “current evidence does not clearly support cardiovascular guidelines that encourage […] low consumption of total saturated fats.” Interestingly, the media did not pick up on the scientific community’s criticisms of the study’s methods in terms of how they chose which studies to include and how they ended up crunching the numbers. Chowdhury and his team did publish a correction to their study, but stated that it “[did] not affect the main conclusions reported in the original article.” despite the new numbers showing a stronger association between omega-3 intake and decreased heart disease risk. An earlier systematic review came to the same conclusion.

It should be noted that in both of the above papers, the bulk of the studies included in the reviews were observational studies, meaning a bunch of people were followed over time, then the researchers tried to figure out whether there was anything in common with the behaviours of people who had similar disease outcomes. These studies can only find correlation, not causation, since many behaviours come together (i.e. people who have higher education tend to eat more healthily, exercise more, not smoke, etc.) it’s impossible to tease out which behaviour is the one that is causing the outcome, or if it’s a combination of these behaviours together.

I find myself agreeing with Examine.com and the Harvard School of Public Health‘s conclusion that saturated fat is neutral – it’s probably not as bad for us as we once thought, but we do know that replacing with unsaturated fats is still a better choice.

“Saturated fats not as bad as once thought; replacing with unsaturated fats still better choice.”

What About Coconut Oil?

This is the part where research on fats gets really confusing. As it turns out, our groupings of saturated vs. unsaturated are far too simple. Remember those carbon chains we talked about in our chemistry lesson? They actually come in different lengths! What’s even more confusing is that all of these different fatty acids coexist – all fats and oils that we find in our diet, whether it’s butter, lard, olive oil or coconut oil, is a mixture of these different unsaturated and saturated fats, with different carbon chain lengths.

Coconut oil is a mostly saturated fat, about 90%, compared to butter, which is about 65-70%, or lard, which is about 45%. Why coconut oil is getting all this attention, however, is because it is about 45-50% lauric acid, a fatty acid with a 12-carbon chain, whereas most of the fatty acids in butter and lard contain 16 to 18 carbons. Lauric acid is considered a medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) and unlike longer chain fatty acids, are absorbed differently. In medical applications, purified MCTs are used for people with malabsorption issues.

What does this mean for your heart? There isn’t a lot of research on coconut oil out there, and many of the claims companies make about coconut oil are based on research on pure MCTs, not coconut oil. For example, while lauric acid by itself seems to increase HDL (good) cholesterol, studies using coconut oil have had mixed results in terms of whether it changes our HDL or LDL (bad) cholesterol levels, if at all.

Omega-6 Fats and Your Heart

Just like not all saturated fats are created equal, not all unsaturated fats are created equal either.

Omega-3 and omega-6 fats are the most commonly known polyunsaturates, and they are also unique in that they are essential, meaning that we can only get them through diet (our bodies can’t make them). Recent reviews appear to support the idea that all polyunsaturated fats confer heart health benefits, especially when they replace saturated fats in the diet.

However, concerns are being raised about the high amounts of omega-6 fats (compared to omega-3) that we are getting in our diet, as omega-6 fats can have pro-inflammatory properties, which can lead to various chronic diseases, including heart disease. This has led some health practitioners to encourage people to avoid vegetable oils that are higher in omega-6, such as soybean, corn, sunflower and grapeseed, which coincidentally are found in many packaged foods. A recent review found mixed results, but many of the studies looked at how much omega-6 was in the blood, not how much omega-6 the subjects ate. Of those that did look at omega-6 in the diet, it either found a benefit or no change, the latter possibly because many of the interventions were short-term.

What this means for you

Fat is confusing! I think it’s safe to say that low fat is out, but before you load up on the butter and the bacon, we do know that vegetable oils, as well as other sources of unsaturated fats, like fish, nuts/seeds and avocado, are still better for you. The debate seems to be shifting more toward where our fat is coming from (there is lots of interesting research on dairy fat, for example) as opposed to saturated vs. unsaturated. While right now the conversation seems to be, “I guess not all saturated fats are bad after all”, I foresee that it might become “I guess not all unsaturated fats are good after all…” And really, it should be, “Let’s stop talking about fat. Let’s start talking about food, eating and living.”

What are your thoughts on fats and your heart?